Can Permaculture Reintroduce resiliency?

Permaculture encourages us to focus on building resilient systems. And not just you and I, but everyone — from permaculture specialists to individuals working in the fields to everyone who benefits from those farming and land management efforts. We live in a community of the Pacific coast of Mexico that is deeply reliant upon its surroundings. This is a community where many people depend on local plant medicine for natural remedies, use an array of herbs for both food and beverage, and count on several tree crops for seasonal fruits, finding a way to reintroduce these plants to small home gardens has been on our mind for a couple of years.

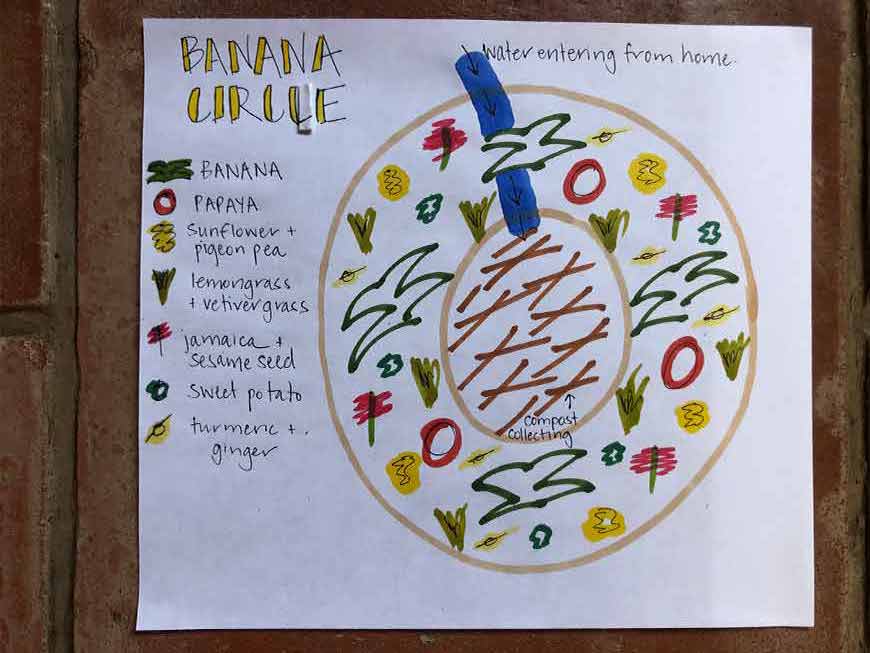

Thanks to a generous donation from two guests, we launched a banana circle project in Juluchuca. The decision to use banana circles to address a crop loss in our community was rooted in a primary permaculture principle known as stacking functions. In simplest terms, stacking functions means every element in a system performs more than one function. Playa Viva’s permaculture lens is to design in a way such that each element serves four, five and six functions. An easy shorthand to remember this concept is 1 + 1 = 3.

Introducing banana circles in town is strategic. It is an opportunity to discuss the value of perennial crops both in the diet and in the soil. The circle itself (described in detail below) creates a space where organic material from around the home can be collected and reused rather than burned. Household water is also captured in the circle, which reduces the frequency of standing water and mosquito habitat in and around the home. Among other functions, it also produces a diverse, nutrient dense harvest as soon as a few months in—a harvest that can be used to supplement the kitchen pantry as well as reduce household costs.

Banana Circle Basics

A banana circle is a classic permaculture technique. It is a blend of, and a relationship between, food production and waste reduction strategies. A banana circle provides a way for you to capture and reuse food scraps, yard waste, and wastewater, while also creating the ideal conditions for bananas and other nutrient-demanding plants to thrive.

Here in Juluchuca and Rancho Nuevo, Playa Viva’s permaculture manager, Amanda Harris, and two graduates of Jóvenes Construyendo el Futuro (a workforce training program that is run by the federal government) planted the first eight banana circles. These first circles were planted with jamaica (hibiscus plants used for fresh juices or in cold salads), papayas, lemongrass, pineapples, melons, achiote (annatto) plants, turmeric and ginger rhizomes, sunflowers and zinnias, sesame and moringa stalks, and passion fruit vines. The tropical harvest that comes out of the banana circles is both color and nutrient dense, and still, the plants are chosen to serve other functions inside the design as well. Root crops ensure we are pulling minerals up to the surface and into our foods; grasses like vetiver stabilize the soil with deep roots; the flowering bush achiote and other striking flowers call pollinators to the space and improve yields; melons and sweet potato vines cover the soil, keeping it cool, humid and full of beneficial microbial life; and tree crops like papaya and banana offer a pillar for the vining passion fruit to climb.

Once a banana circle begins to receive its intended grey water runoff and a little bit of care through harvest and dropping off organic material, the intention is that the circle sustains itself. Crucial to this success though, is to be sure to include family members in the design, the labor, the selection of the plants (based on their diets and health needs), and the planting of the banana circles. We asked each household to have one adult and one child participate at some level, and often the whole family gathered around to observe, dig, laugh, question, and plant.

Progress, Even While Pressing Pause

It is our hope to continue installing these mini food forests/compost pits in several more homes between Juluchuca and Las Placitas, which is up the watershed. Word is out, and some families are even preparing spaces for when we feel safe, informed, and comfortable interacting more closely with our neighbors again. Meanwhile, we are trying to understand and respond to two observations made during this phase one smaller installment:

- Our Playa Viva permaculture team thought the banana circles would address and reduce the burning of organic material in and near households, which it does. What we did not account for was the (high) volume of water used in a local household. The mix of organic material and water, like all systems, must find an equilibrium. Too little water, the plants do not grow; too much water and we create health concerns by way of mosquito larvae. Currently, two compost pits retain water in a way we did not anticipate. We would like to see the water absorbed into the soil differently and think that by encouraging families to add more organic material to the pit, we can help improve the absorption rate and create the balance the banana circles craves.

- Understanding the saturation capabilities of the soil is increasingly important during this shoulder season. While we do not receive much rain to this part of the coast, we are approaching the months where at least some rainfall is expected and the land becomes unexpectedly hydrophobic. New quebradas (streams) and rios (rivers) present themself every year in Juluchuca, and we will have to monitor the placement of each banana circle to make sure they can withstand the influx of water that may pass over them. and through the homes and living spaces where our community members live.

In permaculture, we call this part of the design process “observe and interact.” This principle recommends that we take a relatively cautious approach, that we make the smallest intervention we think necessary to make the change we want, and then we closely and patiently observe the results. We have the opportunity to learn from this pause in our project, and we’re excited to brainstorm among our team and the eight families.

We’ll keep you in the loop as we apply a few simple solutions with the intention of increasing nutrient upcycling—resulting in more food coming from each banana circle.