I’ll never forget when a guest asked me the question,

“Was this fish caught today?”

Her head turned toward the sea as she watched a local fishermen stroll by on the beach. She asked, “did one of these local fishermen catch it?”

I was totally unprepared to answer her question.

Seafood had actually been on my mind since I arrived at Playa Viva nearly one year ago. My master’s degree is in the very subject—marine resource management—so Playa Viva’s involvement with local fisheries was something I had been wondering about. Before I knew how to fully answer her question, I was hoping for the best, but I also knew that around the world fisheries are in a precarious state, how difficult they can be to manage and how difficult it is to trace where your seafood is actually coming from.

Despite the challenges, I knew I had to and wanted to investigate the answer.

As part of my duties to ensure Playa Viva is on track to achieving its regenerative goals, I decided that I needed to do some research to be able to give that guest, and all our guests, an honest answer. I started by asking our chef where our seafood comes from, what he purchases and why. He assured me that he only orders fish that he knows to be native to the region and knew about some local cooperatives down the road but that we didn’t purchase directly from them.

I decided to seek some expertise from one of our partners, Katherina Audley from Whales of Guerrero Research Project, who has been living and working in the Zihuatanejo area’s fishing communities for nearly two decades. When I mentioned to her our seafood purchasing list in passing, her immediate reaction was a little alarming–something I had feared. She asked me to send her a list and would look at it in detail. Her response:

“Now that I see this list, I realize recommendations, etc. are more nuanced than I realized before. What needs to happen is to go to the market in Petatlán and talk to the vendors there. Ask them where the fish comes from and how they catch it. Catch method and how far away the fish comes from change how wise each fish is to consume. If someone can go to the market in Petatlán and map out the chain from catch to table for the different kinds of seafood, and also get copies/pictures of fishing permits from local fishermen, we will be able to move forward with creating a more sustainable fishery. Can you go to the market in Petatlán and do this research?”

I could, but I knew that I needed help.

While recruiting for a volunteer for La Tortuga Viva (our local sea turtle sanctuary) I came across Romain Langeard, a prospective candidate from France who had a background and experience in marine conservation and development, including conducting vulnerability assessments with the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in Burmese fishing communities. Instead of working with the turtle camp, I proposed and offered the position to help conduct the “Seafood Sourcing Sustainability Assessment”, better known now as the “SSSA”. Romain accepted the terms and began work for the project this past April.

The project had two main goals:

1 – To evaluate the sustainability of the seafood served at the hotel, but also

2 – To shed light on the state of fisheries in our area and identify potential ways Playa Viva can be a leader in creating change that supports local sustainable fisheries.

Our findings weren’t very pretty … but first, let me give you some context.

Playa Viva is located about 45 km south of the city of Zihuatanejo, a popular tourist destination with a population of around 200,000 people. Before becoming a popular tourist destination in the 1970s, Zihuatanejo existed for hundreds of years as a remote, sleepy fishing village. In 1971 the Mexican government invested in a large infrastructure project to expand and rehabilitate Zihuatanejo, as well as develop the area to its north, Ixtapa, as a resort destination (1).

Over the last 40 years, the infrastructure needed in this area to satisfy a growing population, as well as both domestic and international tourist needs, have all caused severe impacts on the environment (2). Poorly planned coastal development has greatly disturbed wildlife habitat and resulted in a loss of biodiversity, as well as drastically decreased water quality (2). These factors, coupled with an increased demand for seafood and with that a rise in industrial fishing, have all caused a steady decline in Guerrero’s fisheries (2,3). Consequently, residents, business owners, local fishermen, and conservation actors are all rightly concerned over the health, resiliency and productivity of Costa Grande’s ecosystems.

During interviews with the fishing communities, fishers stated that some of the main barriers to responsible fishing is the lack of demand for a sustainable product and poor enforcement by fisheries authorities. The fishers are numerous and demand is often inconsistent and fluctuates greatly depending on seasonal tourism. Therefore, due to inconsistent demand, economic pressures felt by the fishers and poor enforcement, the tendency to overfish is high. In turn, this has resulted in an attitude of

“Why should I follow the rules if nobody else is?”

Mexico is both party to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and a member of the FAO, demonstrating their long-term commitment to ensuring responsible use and development of marine resources. Through these commitments, Mexico recently developed a long-term strategy for sustaining fisheries in Mexico at the national level (4).

However, based on our initial findings, while fishing legislation exists on paper at the local, national and international level, poor enforcement, monitoring, and thus compliance within Mexico, particularly in Guerrero, renders them almost ineffective.

Nevertheless, while enforcement of (and thus compliance with) regulations is poor, all cooperatives expressed grave concern over the health and prosperity of fisheries. One fisher commented:

“The biggest problem in all the cooperatives is that there is not enough fish. The fish are almost gone.”

In response to this issue, some of the cooperatives have actually implemented some of their own conservation actions. The cooperative of La Barrita has established a rotation of no-take-zones in their respective fishing area and restrictions on certain species depending on the time of year. The cooperative in Barra de Potosí doesn’t (or tries not to) fish during reproduction periods. However, they said it was challenging to get all the fishers in the cooperative to comply.

So, what did we find?

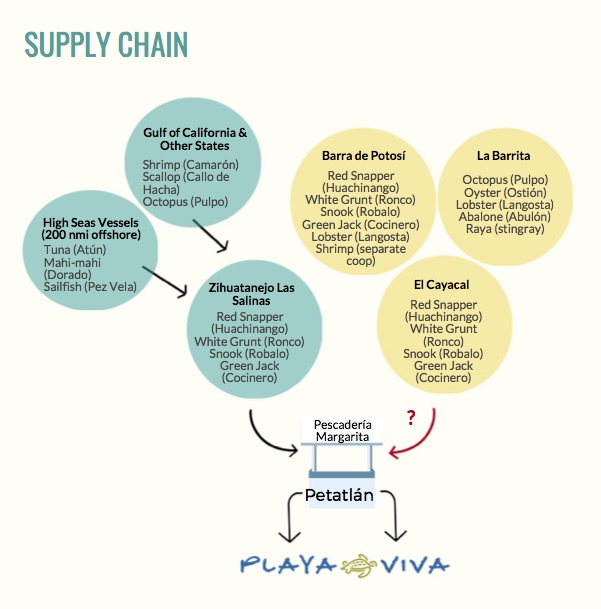

Playa Viva’s seafood is mainly purchased from a middleman supplier in Petatlán (“Pescadería Margarita”), a town of about 18,000 people located 13 km from the hotel. Most of the products purchased from the supplier in Petatlán originate from another supplier in Zihuatanejo, whose products originate from various parts of the country or from foreign and domestic fishing fleets on the high seas. Only some species, such as the more coastal species, like red snapper, originate more locally.

It was difficult for the supplier to confirm with certainty where each fish originated. This low traceability at the market makes it all the more difficult for a business like Playa Viva to know when, where and how seafood products were harvested.

Additionally, we discovered that there was a lack in education among Playa Viva staff on sustainable fisheries topics, which has made it more difficult to make responsible seafood choices. Unfortunately without this knowledge, the hotel was unable to understand the impact of their purchasing patterns.

Consequently, the hotel has unintentionally purchased species whose ecological status is either unknown or depleted, as well as purchased species whose capture methods do not comply with local regulations.

Given the types of seafood purchase and the lack of traceability, we concluded that the seafood at the hotel is unfortunately not sustainable.

As you can see, even though Playa Viva is located directly on the beach with fishing cooperatives just down the road, tracing seafood is often nuanced and complex.

Nevertheless, while the future of Costa Grande’s fisheries may look bleak for now, there is an incredible opportunity to impact the way fisheries are managed locally.

Playa Viva is committed to serve as a model for change and to help create that change in their ecosystem. Romain and I spoke with a lot of fishermen throughout this project and feel that Playa Viva is in an ideal position to work with local fishing cooperatives to begin to solve the “lack of demand for a sustainable product” problem identified by local fishers.

Playa Viva is committed to serve as a model for change and to help create that change in their ecosystem. Romain and I spoke with a lot of fishermen throughout this project and feel that Playa Viva is in an ideal position to work with local fishing cooperatives to begin to solve the “lack of demand for a sustainable product” problem identified by local fishers.

Naturally, it will take some steps to get there.

1. Implement a sustainable sourcing strategy

The biggest need the hotel has is a strategy for sustainable seafood purchasing. The lack of understanding about sustainable fisheries prevented Playa Viva from developing a sustainable purchasing strategy, which inevitably and undoubtedly led to unsustainable purchases. We suggest the new strategy to include: 1) finalizing research on all available legislation and stock status information, 2) supporting management and kitchen staff in adapting purchasing practices and menus through educating them about sustainable fisheries (and supporting in communicating these practices to guests), and 3) identifying and building new and existing relationships with local producers.

2. Lead the creation of a responsible seafood guide

Once Playa Viva has a sustainable purchasing strategy in place, the hotel can be in a keen position to promote the demand for a more sustainable product. Playa Viva could play a key role as a catalyst for positive change in the local ecosystem. The hotel could promote sustainable fishing and responsible purchasing practices through leading the creation of a “responsible seafood purchasing guide”. Katherina and her Whales of Guerrero Research Project have already expressed interest in a partnership with Playa Viva in developing and distributing this guide to other tourism actors, businesses, and individual consumers in the area.

More resources will be required

To successfully implement these two recommendations, we’ll need to bring in someone to support the Playa Viva team in implementing a strategy and also lay the groundwork for the creation of a responsible seafood guide.

If funds can be garnered to support the next phase of this project, Playa Viva has great potential to become a leader in sustainable sourcing, help promote the regeneration of Guerrero’s fisheries, and become a true promoter of regenerative development practices.

Time is of the essence: it will take some work, but the regeneration of a degraded ecosystem is entirely possible. This region can once again be a resilient and thriving ecosystem, where fishing provides benefits for both fisher and consumer alike.

Fishing boats in El Cayacal

If interested in supporting the next two phases of this project, please contact David Leventhal at david@playaviva.com. Or, please donate to our regenerative trust (please write in the comment space it is for the sustainable fisheries project).

If you would like to read the full version of the report, you can download it here: PV Seafood Sustainability Assessment_Aug2017_v2.

A report synopsis can be downloaded here: SSSA-brief-v2.

References

- World Bank (1983). Project Performance Audit Report: Zihuatanejo Tourism Project and Tourism Development Project.

- Ortiz-Lozano, L., Granados-Barba, A., Solís-Weiss, V., & García-Salgado, M. A. (2005). Environmental evaluation and development problems of the Mexican Coastal Zone. Ocean & Coastal Management 48(2): 161-176.

- Kennett, D. (2007). Human Impacts on Marine Ecosystems in Guerrero, Mexico. In: Ancient Human Impacts on Marine Environments. T. C. Rick and J. M. Erlandson, University of California Press, Berkeley.

- SAGARPA (2016) Strategy for Biodiversity Mainstreaming: Fisheries and Aquaculture (2016-2022). Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Rural Development, Fisheries and Food.